On Racial Equity: Lawrence Berkeley National Lab Town Hall

Good afternoon, everyone. I’d like to thank Mike Witherell for inviting me. It’s great to connect with the Berkeley Lab community and learn more about the incredible work you’re doing.I always appreciate connecting with organizations that share some of our UC Davis values. I’m talking about a spirit of collaboration and a mission to tackle some of the world’s greatest challenges. At UC Davis, we take pride in being highly collaborative. We distinguish ourselves by focusing on the nexus between disciplines. Our greatest strength as a research institution is our capacity to combine the talents of researchers from different fields and explore the links between them. At Berkeley Lab, you call this “team science.” Our institutions have a long history of collaboration, going back more than 25 years when the Berkeley Lab was beginning its role in advanced photon science at the Advanced Light Source. Our faculties have partnered on climate research, energy, predictive agriculture, and much more. They include people like Pam Ronald, who was elected to the National Academy of Sciences for her revolutionary work in plant pathology. She has had a significant impact forging collaboration and discovery across both of our organizations. She’s a faculty scientist in the Berkeley Lab’s Environmental Genomics and Systems Biology Division and a UC Davis distinguished professor. Professor Ronald is also scientific lead of plant pathology at JBEI, where she was part of a team that successfully used CRISPR to genetically engineer rice with high levels of beta-carotene. It’s my hope that we can strengthen our connections and build on this spirit of collaboration.

I was asked to share some of my diversity story. I’ve spent much of my career working to increase diversity on college campuses and in the workforce, particularly in STEM fields. Today, that’s more important than ever. The events of recent months have only reaffirmed the need to build an inclusive society, one that recognizes and respects people of all backgrounds and experiences. I’m talking about the disproportionate negative impact of the pandemic on people of color. And also the nationwide social unrest following the police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis in May. George Floyd joins a long list of unarmed People of Color, whose names you will recognize. Breonna Taylor, Trayvon Martin, Tamir Rice, Oscar Grant. Michael Brown was fatally shot by police in Ferguson, Missouri in 2014. That incident happened 2 miles from where I grew up in St. Louis.

Each time this has happened, I’ve thought: “It could have been me.” At a traffic stop, no one knows I’m Chancellor of UC Davis. No one knows I have a Ph.D. I’m just a Black man in a car. As an African American man, there are so many incidents of “microaggressions” that you experience throughout your life and career. Sometimes you become numb to them, but then something like the killing of George Floyd happens and it brings everything back to the forefront. You think about the times when you were treated in a questionable or different way. And you wonder: Was that because I’m Black or was it something else? Is it just normal behavior around here? And you just never know what the truth is.I’ll quote James Baldwin. In 1961, he spoke about being Black in America. “To be a Negro in this country and to be relatively conscious is to be in a state of rage almost, almost all of the time.” I’ve often felt that very viscerally. Baldwin also argued that “a complex thing can’t be made simple.” Fundamentally, I think that’s the challenge of the diversity, equity and inclusion work today. In 2020, it’s a tall order to tackle a problem that has persisted for so many years. We need a wide range of initiatives to address the inequities that persist for women and people of color, especially in the STEM fields. And it will take a long-term commitment.

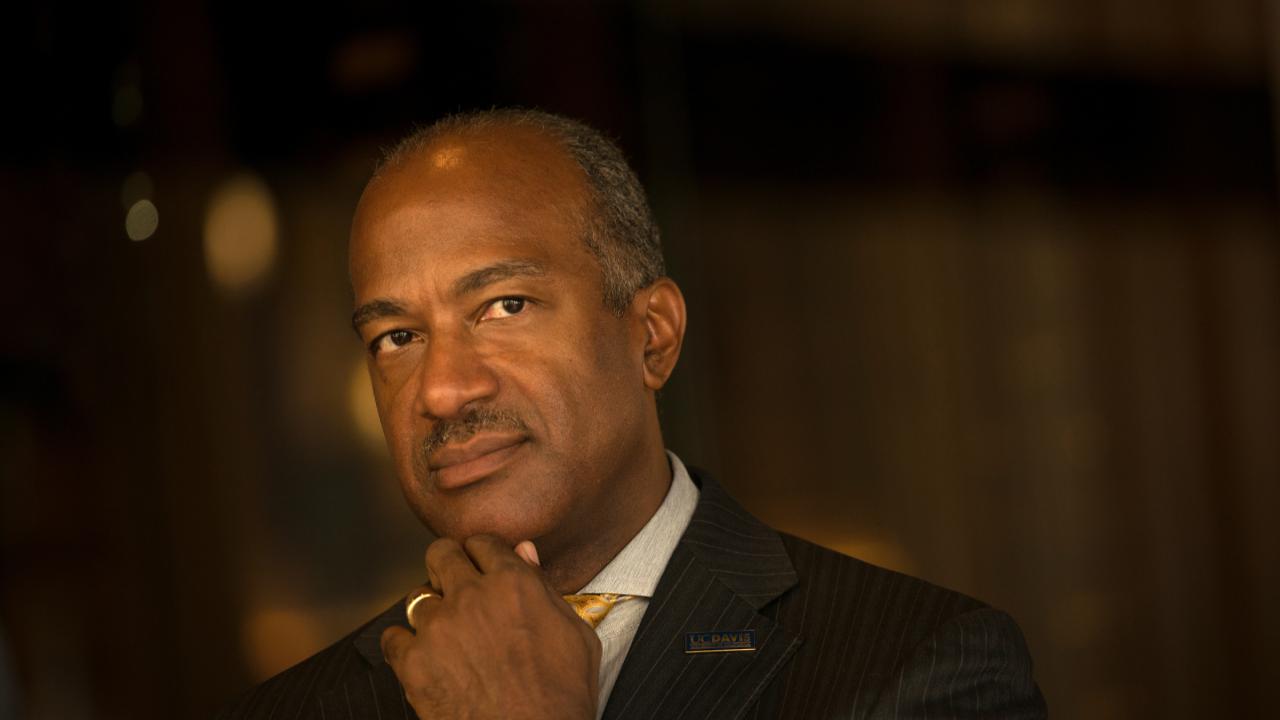

Still, I think we have a unique opportunity in this moment to create change. All across the country, we’ve heard the calls for social justice. In these polarizing times, embracing diversity and inclusion is central for our humanity and evolution as a society. Each one of us must do what we can to eliminate racism, sexism, and other negative influences on our progression as a nation. And to be clear, when I refer to diversity, I’m talking about the full array of nationalities, the full spectrum of socioeconomic and cultural backgrounds. As well as a wide variety of political views and gender identities. And a rich diversity of talents and skill sets. I want to acknowledge Mike Witherell and your leadership team for wanting to have honest conversations about diversity and inequity. It’s important that we talk about these issues, even when it sometimes can be uncomfortable. Now, I want to share some of my own journey. So, let me start at the beginning.

Well, we don’t have to go quite that far back. But I wanted to make a few points about my formative years and what motivated me to become an engineer. And to work throughout my career to increase diversity in STEM, both on college campuses and in the workforce. As I mentioned, I grew up in St. Louis. That’s also where I was born. When I look back on my early childhood, I see that Legos and Erector sets were the building blocks for my future as an engineer.

And once I discovered “Star Trek,” my imagination went into hyperspace. Through the family TV, I witnessed a fantastic universe of phasers and teleportation. The first time I saw a flip-phone was on Star Trek. iPads and tablet devices also look quite a bit like the PADD devices used by the Starfleet’s crew.

When I wasn’t watching Star Trek, I devoured comic books, learning all about superheroes and their special powers. (You may be surprised to learn that my comic book collection has more than 30,000 titles.) There are a lot of things in Marvel comics – and movies – that might spark the interest of a budding engineer. In fact, the UC Davis Department of Chemical Engineering and Materials Science offers a course that delves into the science of superheroes. Students get to analyze the scientific credibility of superhero physics. Think about Iron Man’s suit, complete with AI, thrusters and weapons. Or the Black Panther’s. It’s made of vibranium, a metal that can store and transform energy. Hypothetically, of course. (On a side note, I want to mention that Marvel screenwriters Christopher Markus and Stephen McFeely are UC Davis alums. They wrote Avengers: Endgame and Infinity War, among others.) Superheroes inspire me. As a researcher, you have to be creative. You have to imagine things that people don’t think are possible. Growing up, I was fortunate that my parents encouraged my creativity. It also helped that I had a strong aptitude for math and science. Education was a core value in the May family – and still is.

My Mom was a groundbreaker. She was among the first to integrate the University of Missouri in the 1950’s. This was during the era of Jim Crow, the laws that enforced segregation in the south and other parts of the country. It seems like Jim Crow laws were from so long ago, but they really weren’t. That was just one generation removed from me. Anyways, when my Mom showed up to the dorms for the first time, the house mother got really upset. She didn’t like that Black girls were going to be living there. She even questioned where they were going to shower. My Mom never gave up, despite the hateful language and other incidents that came her way. She didn’t let anyone get between her and her goal of earning a college degree. I learned quickly to follow her example when I started as an undergrad at Georgia Tech. I had to stay focused and learn to rise above adversity. On my very first day at the dorms, I found “N-word lover” written on my roommate’s name card on the door. My Mom and Dad were upset and nervous when they saw this. But I said it could be worse. I’m glad to be living with the “lover,” rather than the person who wrote this on the door. So, I persevered and pressed on.

My Mom remains one of my greatest sources of inspiration. I think of what she endured in her pursuit of higher education, and even now, I carry her lessons in tenacity and self-determination. I had another awakening while I was earning my degree in electrical engineering. I’d look around the laboratories and lecture halls and realize I was usually the only Black person in the room. That became my motivation to make a difference. I looked for people to inspire and mentor me.

As an undergraduate student, I saw a whole new world of possibilities that were embodied by the man pictured here. This is Dr. Augustine Esogbue, the first black engineering professor at Georgia Tech. He was also the world’s first black Ph.D. in industrial and systems engineering and operations research. He had it all … the sharp clothes, the fancy cars, the giant intellect. We all wanted to be like “Dr. E.” He took me under his wing, and my world opened up. I saw for the first time a Black man finding success in the engineering.

I think everyone needs some help along the way and to be able to see themselves in these roles. So, I’m a huge proponent of mentorship. One of my favorite quotes about mentorship comes from the former surgeon general, Joycelyn Elders, who said, “You can’t be what you don’t see.

Along with finding mentors, I wanted to build community with my peers. I found an incredible source for that with the National Society of Black Engineers. This organization was founded in the mid-1970s, and I joined a few years later as an undergrad at Georgia Tech. The NSBE was a game changer for me. It helped me connect with others who had the same passion for engineering. We could relate to each others’ struggles and stories of feeling isolated. We were looking for mentors and wanted to help others along the way as well. By the way, the same is true on our college campuses and in the workforce. If we want to increase diversity, it’s important to build community. Underrepresented groups are looking for a sense of belonging – and a reason to stay.

Here’s a flashback to my graduation from UC Berkeley, where I earned my masters and Ph.D in electrical and computer engineering. In fact, when I got my Ph.D. from Berkeley in 1991, I was one of only about 31 African Americans that year who had earned a doctorate in the field of engineering. I’m talking 31 in the entire United States! All of these experiences helped motivate me to increase diversity. And we had great success with some of the programs I helped to create. At UC Berkeley, I helped form the Black Graduate Engineering and Science Students. It was clear that African American students were abysmally underrepresented in graduate school, especially in the STEM fields. I’m also proud to say that I had a hand in creating SUPERB, which stands for Summer Undergraduate Program in Engineering Research at Berkeley. Our goal was to bring together a diverse, talented pool of students and motivate them toward graduate school. The SUPERB program continues to this day, as shown by these recent participants.

When I joined the faculty of Georgia Tech in 1991, I wanted to re-create the spirit of SUPERB. So, I helped create the Summer Undergraduate Research in Engineering/Science – otherwise known as the SURE program. With the help of a $3 million grant from the National Science Foundation, every summer we hosted underrepresented students at Georgia Tech to perform research. Ultimately, our goal was to see them pursue a graduate degree. And that’s exactly what happened. During that time, we saw over 73% of SURE students enroll in graduate school. I also served as co-creator and co-director of two other programs: the Facilitating Academic Careers in Engineering and Science (FACES) and the University Center of Exemplary Mentoring (UCEM) programs. The goal for both of these programs was to increase the number of underrepresented Ph.D. recipients from Georgia Tech. I’m proud to say we were successful. Over the duration of FACES, more than 400 people of color received Ph.D. degrees in science or engineering at Georgia Tech. At the time, that was the most in such fields in the nation.

My Dad used to say that one day I’d be president. That didn’t happen obviously, but I did get to meet one or two of them. In 2015, I received the Presidential Award for Excellence in Science, Mathematics and Engineering Mentoring from President Barack Obama. This was due to my efforts in supporting underrepresented students at Georgia Tech and the successes we achieved. Receiving that award from President Obama was definitely a career highlight!

Let me shift gears and talk about why I think diversity is important in STEM, for both academia and in business. I believe deeply that we need to prepare students for a workforce that’s increasingly diverse and increasingly global. Businesses, laboratories, universities are going to need to fill the shoes of the current workforce. And there’s a competitive need to sustain U.S. global leadership in innovation. “Diversity” isn’t just a good buzzword. It’s at the root of innovation and technological advancement. The greater diversity we have in research, the more likely we can make discoveries and solve problems. A wide mix of backgrounds, experiences and ideas are necessary to make that happen efficiently and robustly. The first airbags in the auto industry almost killed women passengers. Why? Because they were tested on crash-test dummies that had male anatomies, which were larger in stature.

We’re finding that some Artificial Intelligence programs used for facial recognition have racial and gender biases. One African-American researcher tested various facial recognition systems while wearing a white mask to hide her features. She found the systems worked better on men’s faces compared to women. She also found they worked better on lighter-toned faces. In fact, she recorded error rates up to 47% for darker skinned women like herself. On a side note, I’d like to add that the researcher here, Joy Buolamwini, was one of my undergraduate students at Georgia Tech.

Here’s a final example that’s a little scary. Another study from Georgia Tech found that people of color are more likely to get hit by a driverless car. Like facial recognition technology, driverless cars may better detect pedestrians with lighter skin than those of us with darker skin pigment.

These are all real practical examples of why diversity, as I said, is not a buzzword. It actually gives better outcomes. If you have diverse design teams involved with some of these examples, I contend and assert that you have better outcomes with the products that are produced. It’s not more scientists that lead to more innovations. It’s more diverse scientists that lead to more innovations. So, I encourage you all to think broadly about diversity, equity and inclusion. Think of how society benefits when many diverse perspectives work together to find solutions to our problems. And most importantly, think about leading by example. That might mean listening to diverse perspectives or working to recruit diverse workforce or team. It could also mean using your own gifts to mentor a rising talent. Together, we can empower the next – more diverse – generation of STEM.